|

| Black Hole Bonanza |

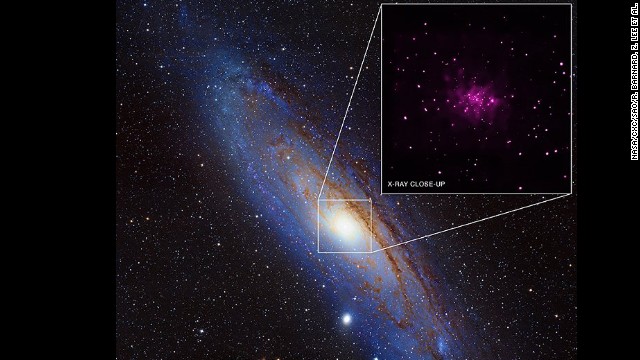

Researchers find 26 possible black holes in Andromeda, a galaxy near our own Black holes can't be seen directly But astronomers can detect material falling into them when they interfere with other stars

You're in no danger of falling in, but a large group of possible cosmic vacuum cleaners have just been identified.

Researchers have come upon 26 possible black holes in Andromeda, a galaxy near our own.

This is the largest number of possible black holes found in a galaxy outside the Milky Way, but that may be because of Andromeda's relative proximity to our galaxy. It's probably easiest for Earth-based scientists to find black holes outside the Milky Way there, said Robin Barnard of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Combining this discovery with previous observations of nine other black hole candidates, scientists can say that Andromeda has a total of 35 possible black holes. The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory made more than 150 observations over the course of 13 years to identify these black hole candidates.

Seven of the new potential Andromeda black holes reside within 1,000 light years of the center of that galaxy. This supports earlier research showing that, near the center of Andromeda, there are an unusual number of X-ray sources.

Black holes can't be seen directly. But astronomers can detect material falling into them when they interfere with other stars.

A black hole is a dense region of space that has collapsed in on itself in such a way that nothing can escape it, not even light.

In a binary system of this nature, a black hole and a star orbit each other closely. Material from the star falls into the black hole and "as it spirals in, it gets hotter and hotter, and faster and faster, and eventually it gives off X-rays, so we see lots and lots of X-rays coming out of it," Barnard said.

The material as it has been swallowed gets incredibly hot, up to about 10 billion degrees. Because of the tremendous amount of energy released, some of the brightest objects in the universe are black holes.

It's hard for scientists to distinguish distant black holes from neutron stars, however.

When a star explodes in a supernova, its fiery death leaves behind either a neutron star or a black hole, which is a more extreme version of a neutron star.

If our own sun were a neutron star, it would be only about 10 kilometers, or 6.2 miles, across, Barnard said. By comparison, as a black hole our sun might be only 2 kilometers across. Black holes of the kind that scientists may have spotted in Andromeda have masses that are typically five to 10 times that of the sun.

Neutron stars have a surface, so falling material pounds onto it, Barnard said. Material rains down at enormous speeds, causing huge explosions and energy emissions.

Billions of years from now, the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies will collide, marking the end of the galaxy as we know it.